Occasionally people have asked me if I think it’s possible to know our own True Will. I don’t know if it is. I have only ever found one answer. It’s what we already did. Because it must be.

It’s a terrible answer, but bear with me.

Most of us prefer to move on from whatever it is that we have been through. At times we need forgiveness, but forgiveness too is aimed towards the future. We do it to liberate one another from past mistakes, hurts, and wrongdoings. Forgiveness is hard, but once it’s done we are free to forget. And eventually we do forget, and begin to move forward again.

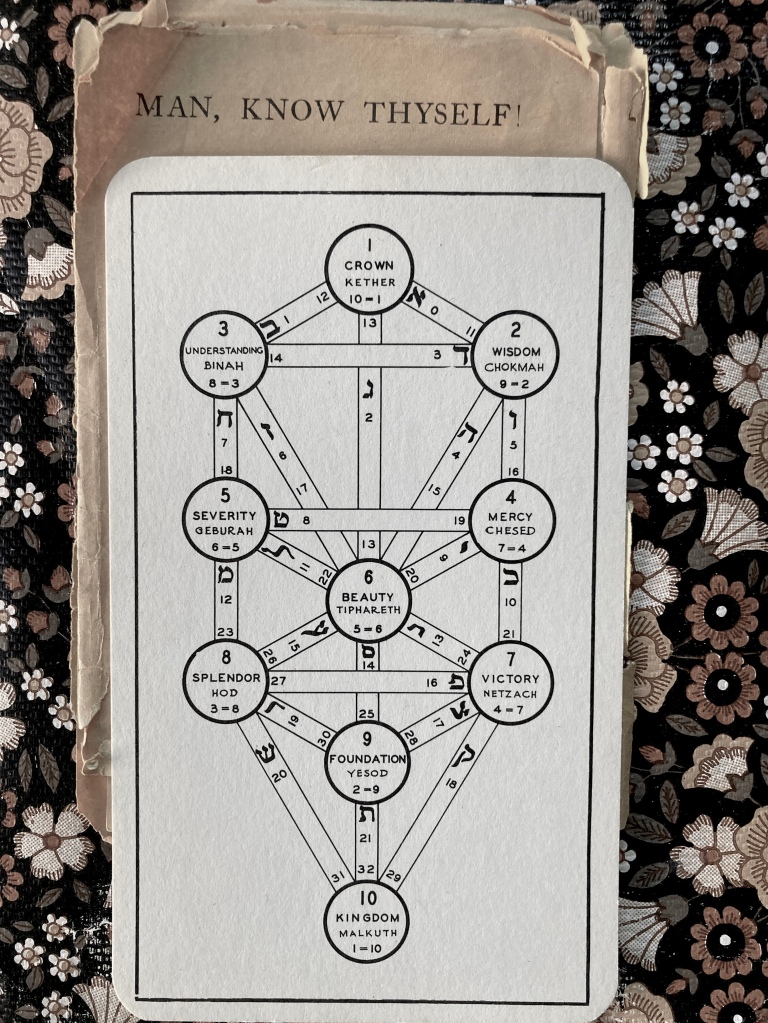

In the formula for Thelema a particularly important word is hidden, but in plain sight. The formula is written in the form of a command:

“Do what thou wilt.”

This could be compared to another well known formula, and command:

“Man, know thyself.”

But Thelema is not a matter of knowing, it’s a matter of doing. Knowing is necessarily oriented towards the past, because we cannot know the future. Doing, on the other hand, is necessarily oriented towards the future, because we cannot do anything about the past.

It is what it is. We are what we did.

First of all – and most of all – Thelema, as a philosophy, asserts the existence of the individual. It does so by suggesting that Will is the guiding principle by which we can understand reality, our relationship to one another, and even to the rest of the universe. The word Thelema means Will, and where there is a Will, there is an individual. Moreover, there is a sign of life.

Individualism is not the same as Thelema. Thelema is not bound to be only an individualist philosophy. Thelema is adaptable to transcendentalist and essentialist ideas, at least as much as it is to existentialist ideas. Meanwhile individualism, as we are used to it today, is usually more existentialist.

The reason for this difference is that Thelema is not only busy with the individual – or unit – whose importance it asserts. Thelema is also busy with its own wild claim. That there is something more than an ordinary Will at work within us, in between us, and deep within nature itself. Thelema claims True Will, and that is something altogether different than the Will that we are used to thinking about. It is different too from the Will of the existentialist thinker, who might be busy thinking about the Free Will of each individual, and therefore each human being’s right to freedom, and individualism with it.

Besides the unit of the individual, Thelema asserts that the unit is in unity with the universe. Naturally this is true – more or less a fact – from a scientific viewpoint. But how to come to terms with this fact, is the business of Thelema. That is what it tries to do, (at least sometimes), and the ambition is not unique. Thelema is not the only philosophy that admits to the truth of the existence, and reality, of individual life forms. Every modern philosophy has to take these natural facts into account, since they are actual facts. This is often in opposition to religion, since religion creates its own account of reality, apart from science. A religious person may deny a scientific fact, and go on to form her own philosophy based solely on religion. An honest philosopher may not. A Thelemite just can’t.

Thelema thrives on the friction formed in the cracks between what is a private experience, and what is an observable fact. What is religion, and what is science? What is superstition, and what is reality? Thelema deals with magic, as well as with reason. It speaks about the imagination, and it speaks about the skeptical mind.

The original founder of Thelema, Aleister Crowley, was perhaps most of all a poet. There aren’t a lot of nice things to say about him. In fact all of it is awful. If we are compelled to listen to him not-so-nice-poetry is what we will get. But we are compelled to listen to him, evidently. Perhaps because something utterly human has always compelled us to listen to drunkards and poets. Personally I believe that I’m drawn to Aleister Crowley’s ideas because there is an essence in them that I cannot resist. That I do not wish to resist. And that is what distinguishes my analysis from an existentialist viewpoint. As an existentialist I might have said that Crowley was a human being, and he had every right to have his own opinion, and every right to make his own meaning out of life. Then I would be done with it, since I would be busy making my own meaning, and asserting my own rights to do so in the process. Busy enough, so to speak, if I was only an individualist. But I’m not, I’m a Thelemite, which means I have made my own meaning out of Thelema. In part it means that I believe each life is born to an essential meaning. I believe this essential meaning emerges from living life. I believe the life of other living beings can and will inform me on the truth of life. I believe this truth, or True Will, is shared by all living beings, past, present, and future. I even believe it exists in fruit flies, which I will come to in a minute.

To an outsider, at first it may seem like Thelema is a lot of hot air, lingo, and secret hand shakes. I guess that must be because at first it is. Art. Mystery. Fantasy. All of the things we love about children when we watch them play, or better yet, play along with them, are the same things, but distorted, that disturb us when we want to get to the truth of a matter, in an adult conversation, but can’t. It seems perpetually hard to discuss the central topics of Thelema, without falling into some, or all, of its traps of dizzy pagan poetry. Even just reading Aleister Crowley sometimes gets you into trouble. He often starts out by telling you what his essay is going to be about, and then slowly but surely changes the subject to cheese, makes you laugh, and ends it on a completely different topic. Let’s not do that. Let’s talk about fruit flies instead.

The fruit fly is enough to be a unit of life. Even a fruit fly must to some extent realize its own self, and it must to some extent realize its own conditions. It must learn about itself, and it must learn about the world. This, in order to achieve its own survival. In depth studies of the behavior of fruit flies* have shown that fruit flies have a natural ”rudimentary” tendency for what philosophers might call Free Will. Scientists describe this trait as a “non-random – yet still unpredictable – decision-making capacity”. Fruit flies have that, which means that in this sense, they have a Will of their own. As a unit of life we are not so different from fruit flies, or from other living beings. Living is not so much an intellectual pursuit, and Will is dependent on intuition, and experience – maybe even more than it is on intellect.** This is an important clue to understanding Thelema. We are left here with the books, but the books were written from experience, and intuition.

This does not mean that Thelema has no intellectual pursuit. Saying that you can’t learn Thelema from books, and you have to go out and have your own experience from “magick”, or from “gnosis” easily becomes just another way to opt out of explaining the basic elements of Thelema as a philosophy. Let’s not do that. Let’s talk about the unit and the universe instead. Where there’s a Will there’s a way.

The lingo of Thelema tells us that there are two major tasks in life. One is the Knowledge and Conversation with the Holy Guardian Angel. The other is the Crossing of the Abyss. In essence this can be translated into two moods – we must realize our own self, and we must realize our own conditions. We must learn about ourselves, and we must learn about the world. But this is not unique for Thelema. This is unique for life. What is unique for Thelema is that it tells us that there is a True Will, rather than a Free Will, underpinning this mission.

So, is there?

Applied to our new friend, the fruit fly, a True Will seems both naturally obvious, and hopelessly elusive. As little as I’m sure of any scientific, or philosophical, proof of Free Will, as little am I sure of any proof of True Will. Yet, a True Will sometimes seems closer at hand, since it requires less choices, but still asserts the importance of the individual, and its capacity to choose. After all there is no choice to be, or not to be, a fruit fly. Or, is there?

Furthermore, the lingo tells us that there is Nuit, and there is Hadit. If we observe our own natural conditions, we might not have to look to the supernatural to find phenomena that these concepts can be applied to. If we translate the expressions of Nuit and Hadit into universe and unit, we are able to observe the expressions of these deities in two important fields of observation – nature, and language. There they are running across the hot summer meadow, humming like bees, swaying like flowers. And there they are, on a dark day indoors, chasing each other through the lines and letters of an old book, half read, half forgotten. There they are, wherever you look for them, the lovers of this world. The lovers hidden inside this world, and not like some other deities, hidden in the next one. Here again, is something to distinguish Thelema from other philosophies, or other religions. Even from other magical practices. The deities, the divine, is in this world. The divine is alive, and we are part of it, participating in it. Whether we realize it, or not, magic is always present. There’s no pie in the sky. There’s only pie right now.

(But maybe, in some way, the pie is eternal.)

Or, at least, that’s how I see it.

Thelema thrives on the friction of these kinds of questions, and observations. What is science, and what is religion? What must I take on faith in order to go on living? What can I observe as a matter of fact, when I look at the lives of other living beings all around me? Am I alive to the fact that every single individual unit of life is unique? And that this uniqueness may be taken as a metaphor for a Holy Guardian Angel, or vice versa? Am I alive to myself? And to how this selfhood may be taken as only a temporary assembly of various materials tossed around in space? But is it just an assembly? Is it really just being tossed around? Am I the work of pure chance? Or is there some deeper truth hidden within my own nature? Who am I? A ray of light floating over this huge dust bin, the Abyss of Everything. What about the rest of me? What is left in me that cannot be substituted, or confused, even when everything has been substituted, and confused, by living? The thing that seems to go on assembling, and go on living, what is that thing? My self? My being? And doesn’t it seem to be very true? True, rather than free?

Very confusing stuff, the unit and the universe. But no matter how confusing it is, I have found it to be a good model for understanding the mission in life that Thelema proposes to its practitioners. The Great Work. The long and arduous journey of making life worth living.

Nuit and Hadit are of course more than just universe and unit. Because they are symbols, and deities, they represent a depth that more average concepts inevitably lack. There is a reason for the mystic to be a mystic. Life is mysterious. What we know is that we don’t know. But there is no reason to mystify. Things are mysterious enough as they are. There are lots of questions. More questions than answers. So much mystery, so much poetry, and so many secret hand shakes later – at the end of the day a few things remain the same for me when it comes to Thelema as a philosophy for living. To be true. To do better than yesterday; that is, to strive. And last, but not least, to always be in love.

I’m not sure if it really is possible to know our own True Will, but I know from experience that looking back can at times be both painful and embarrassing. I try to live in such a way that I can bear to look back at life. But sometimes I can’t bear it.

I’m not sure if we are actually making proper choices in life, or if we are just living, but I assume my living is not completely random. I think it’s guided by something.

This something might as well be called True Will.

*

https://www.reuters.com/article/us-flies-freewill-idUSN1532077920070516/

**

https://www.jstor.org/stable/2940445?seq=1